Character: The Heart of Your Novel

The following is an excerpt from WD Books’ Creating Characters: The Complete Guide to Populating Your Fiction, a comprehensive reference to every stage of character development. In the book, you’ll find…

The following is an excerpt from WD Books' Creating Characters: The Complete Guide to Populating Your Fiction, a comprehensive reference to every stage of character development. In the book, you'll find timely advice and helpful instruction from bestselling authors such as Nancy Kress, Elizabeth Sims, Orson Scott Card, Chuck Wendig, Hallie Ephron, Donald Maass, and James Scott Bell. Together they walk you through the important steps in bringing your fictional cast to life. In this excerpt from Joseph Bates (originally from his WD Book, The Nighttime Novelist), you'll learn exactly why it's your character that should be the start, and heart and soul, of your novel. Without a character that is in someway relatable and wholly understandable, there's a chance your story, no matter how smartly written, could fall flat.

* * * * *

In Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, an unnamed father and son, survivors of some never-specified apocalyptic event, head south by foot in the hopes of finding some, any, more sustainable world than the wasteland around them. “Going south” is thus the stated, external goal of the two characters; it’s what they hope to accomplish in the most basic sense. And the external conflicts they face along the way—from desperate individuals hoping to steal their few resources to roving gangs of marauders rumbling up the road in diesel trucks to the hostile, unforgiving terrain itself—all stand in the way of that goal.

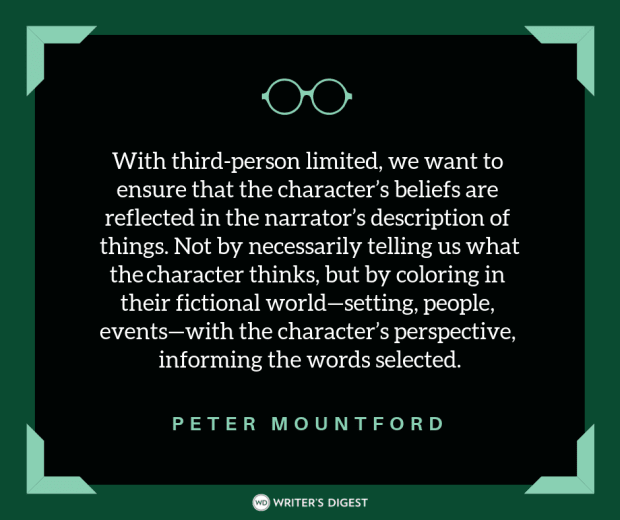

Does stating and understanding the external goal and conflicts of the story reveal the gripping emotional experience of reading The Road? Absolutely not. The external goal and conflict are aspects of pure plot, the general “what happens.” And the external motivation and conflict as stated here—characters wanting to get somewhere and being hindered—are familiar to us, forming the basic plotline of everything from The Odyssey to The Wizard of Oz to Charles Frasier’s Cold Mountain to the Steve Martin movie Planes, Trains, and Automobiles. Reduced to these terms, the external motivation and conflicts of McCarthy’s novel seem unremarkable. But The Road is a remarkable, even unforgettable, book, and what makes it so is the way the external motivation and conflict parallel, complicate, and deepen our understanding of the characters’ internal motivation and conflicts.

We find hints at the internal motivation of the characters by looking more closely at the stated external goal: The father and son are heading south in the hopes of finding a more hospitable climate. But the bleak, unrelenting environment McCarthy sets up in the novel’s opening pages—with its “ashen daylight” and “cauterized terrain”—makes it clear that there probably isn’t any place untouched by the cataclysm; the burnt-out condition of the world seems all-encompassing. If this is the case, and their stated goal of finding a more inhabitable environment is unattainable, what’s really keeping the characters (and story) moving forward, and why do we care?

If you’ve read the book, then you know the answer: The father is using the goal of heading south as a way of holding onto the slimmest idea of hope. And the reason he’s doing this is simple: He’s trying, against all conceivable odds, to keep his young son alive. This is the father’s internal motivation, the reason the events in the book are meaningful to him and, as a result, meaningful to us.

What would you do to protect the life of the ones you love? Could you steal to keep them alive? Could you take a life? Could you keep one foot moving in front of the other when there is, in fact, nowhere safe on earth you can go? These are all questions of internal conflict, questions that, along with the internal motivation, make the external motivation and conflict matter. And these are also the questions we find ourselves asking as we read the novel; you need to never have been in a postapocalyptic wasteland to find something relatable, and heartbreaking, in the father and son’s journey.

This connection to character and what’s personally at risk was a crucial component of McCarthy’s initial creative spark, as he revealed in an interview with Oprah Winfrey:

My son John and I … went to El Paso, and we checked into the old hotel there, and one night John was asleep, it was … probably about two or three o’clock in the morning, and I went over and I just stood and looked out the window at this town. … I could hear the trains going through and that very lonesome sound, and I just had this image of what this town might look like in fifty or a hundred years. I just had this image of these fires up on the hill and everything being laid waste, and I thought about my little boy.

What sparked the idea for The Road was nothing more than McCarthy’s looking out his hotel window at the darkened city, and at that moment two things converged: First, he imagined the city burnt-out and decimated. Then he looked at his young son sleeping in bed and found himself wondering, if the world were in ruins, could he protect his son? From this seemingly simple wandering thought, The Road was born—an apocalyptic story and vision, and also the story of a father wondering if he were fully capable of protecting his child from the harsh world.

This is precisely the way our own novel ideas should start: not just with an external idea, conflict, and motivation, but with a resonant and relatable view of who the characters are, what it is they truly want, and what they would do to achieve it. Without considering your character in such terms, you run the risk of writing a novel in which things happen but affect no one, and as a result the events will resonate with neither your reader nor you as the author. When an understanding of character informs and is at the heart of your work, you’ll find that the world you’ve created is one that the reader finds engaging, terrifying, touching, but above all familiar.

* * * * *

Looking for more valuable information on characters and writing novels or short stories? Look no further than Crafting Novels & Short Stories: The Complete Guide to Writing Great Fiction. This book, similar to Creating Characters, pulls the writing of several WD authors, from both the magazine and books, to pick their brain on writing a truly great story. Crafting Novels & Short Stories covers everything from Plot and Conflict to Setting and Backstory to Description and Word choice, and much more.

Cris Freese is a technical writer, professional book editor, literary intern, and the former managing editor of Writer's Digest Books. Cris also edited the annual guides Children's Writer's & Illustrator's Market and Guide to Literary Agents, while also curating, editing, and writing all content for GLA's online companion. crisfreese.com