Why “Show, Don’t Tell” Is the Great Lie of Writing Workshops

I’m honored and excited today to be bringing you a guest post by critically acclaimed novelist and writing instructor Joshua Henkin. I first discovered Henkin’s work years ago when I…

I’m honored and excited today to be bringing you a guest post by critically acclaimed novelist and writing instructor Joshua Henkin. I first discovered Henkin’s work years ago when I received an advance copy of his novel Matrimony at Book Expo America, and I later enjoyed having him contribute a thought-provoking essay on the art of storytelling to Writer’s Digest magazine (in fact, two of his writing tips from that piece made our Top 20 Writing Lessons From WD list in 2009).

I invited Joshua Henkin to be our guest this week in celebration of the release of his brand-new novel, The World Without You. His topic of choice—a sound argument for breaking the “Show Don’t Tell” rule of writing—is a perfect extension of my post last week about How to Break the Rules of Writing.

Joshua Henkin is the author of the novels Matrimony, a New York Times Notable Book, and Swimming Across the Hudson, a Los Angeles Times Notable Book. His new novel, The World Without You, has just been published by Pantheon. His short stories have been published widely, cited for distinction in Best American Short Stories, and broadcast on NPR's "Selected Shorts." He lives in Brooklyn, N.Y., and directs the Master of Fine Arts program in Fiction Writing at Brooklyn College. You can connect with him on Facebook or follow him on Twitter @JoshuaHenkin.

Why “Show, Don’t Tell” Is the Great Lie of Writing Workshops

OK, let’s dispense with the obvious—namely, that there is a kernel of truth to the old saw “Show, don’t tell.” Fiction is a dramatic art, and you need to dramatize, not simply state things. The sentence “John was a handsome man” is not a handsome sentence, and though a writer is welcome to use it, she shouldn’t think it will do much work for her. Similarly, in the first workshop I ever took as a student of writing, when someone wrote “An incredible feeling of happiness washed over her,” the teacher said, “First of all, get rid of the ‘washed over’ cliché, and second of all, if in the course of an entire novel you can evoke an incredible feeling of happiness, then that’s a major accomplishment.”

But it doesn’t follow from this that a writer should never say a character is handsome or happy. It doesn’t follow that all a writer should do is show. To my mind, the phrase “Show, don’t tell” is a wink and a nod, an implicit compact between a lazy teacher and a lazy student when the writer needs to dig deeper to figure out what isn’t working in his story.

A story is not a movie is not a TV show, and I can’t tell you the number of student stories I read where I see a camera panning. Movies are a perfectly good art from, and they’re better at doing some things than novels are—at showing the texture of things, for instance. But novels are better at other things. At moving around in time, for example, and at conveying material that takes place in general as opposed to specific time (everything in a movie, by contrast, takes place in specific time, because all there is in a movie is scene—there’s no room for summary, at least as we traditionally conceive of it). But most important, novels can describe internal psychological states, whereas movies can only suggest them through dialogue and gesture (and through the almost always contrived-seeming voiceover, which is itself a borrowing from fiction). To put it more succinctly, fiction can give us thought: It can tell. And where would Proust be if he couldn’t tell? Or Woolf, or Fitzgerald? Or William Trevor or Alice Munro or George Saunders or Lorrie Moore?

And yet day after day we hear “Show, don’t tell.” And there’s real fall-out. I see it constantly among my students, who are nothing if not adjective-happy. Do we need to know that a couch is a “big brown torn vinyl couch”? We are writing fiction, not constructing a Mad Lib. Yet writers have been told to describe, and so they do, ad nauseum. It’s like the sentence that was popular in typing classes—“The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dogs.” Well, this is a good typing sentence (it contains every letter of the alphabet), but it’s a bad fiction sentence.

If you ask me, the real reason people choose to show rather than tell is that it’s so much easier to write “the big brown torn vinyl couch” than it is to describe internal emotional states without resorting to canned and sentimental language. You will never be told you’re cheesy if you describe a couch, but you might very well be told you’re cheesy if you try to describe loneliness. The phrase “Show, don’t tell,” then, provides cover for writers who don’t want to do what’s hardest (but most crucial) in fiction.

Besides, the distinction between showing and telling breaks down in the end. “She was nervous” is, I suppose, telling, whereas “She bit her fingernail” is, I suppose, showing. But is there any meaningful distinction between the two? Neither of them is a particularly good sentence, though if I had to choose I’d probably go with “She was nervous,” since “She bit her fingernail” is such a generic gesture of anxiety it seems lazy on the writer’s part—insufficiently imagined.

—Joshua Henkin

Announcing the Winner of Our Giveaway

Speaking of breaking the rules of writing: Thanks to everyone who left comments embracing the spirit of breaking the writing rules. The randomly chosen winner of a free copy of The Rule-Breaker’s Issue is: Ivye. (Ivye, please email writersdigest [at] fwmedia [dot] com with your mailing address, and we’ll get your issue out to you right away!

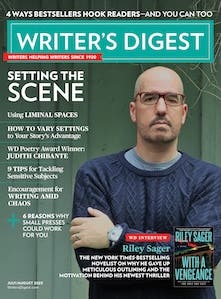

Preview and/or order the full July/August Writer’s Digest here, find it on your favorite local newsstand, or download the complete issue instantly.

Jessica Strawser

Editor, Writer’s Digest Magazine

Follow me on Twitter: @jessicastrawser

Like what you read from WD online? Subscribe today, so you’ll never miss an issue in print!

Jessica Strawser is editor-at-large for Writer's Digest and former editor-in-chief. She's also the author of several novels, including Not That I Could Tell and Almost Missed You.