Her Kind: A Writer’s Personal Comps

Author Jen Michalski shares her difficulty with writing comps for her novel and discusses books that elicited a response.

What are my comps? If you’re a writer, you know the nightmare that is finding the right comps, or books similar to your own. If you’re not a writer, in the publishing world, a comp is marketing shorthand for where you think your book should be categorized in the market: “My dark comedy is like Heathers meets Cocoon” or “my trilogy is a retelling of Wicked but at Hogwarts.” Figuring out my comps is one of the most difficult things I’ve ever had to do as a writer (in fact, my agent was the genius behind the comp of my current novel, All This Can Be True, which she described to its eventual publisher as “a queer retelling of While You Were Sleeping”).

I think part of the problem with comps (or even just telling a potential reader what your book is about) is that although we might go in with a clear idea of the book we want to write (a retelling of Wicked but at Hogwarts), sometimes we write a book that is not comparable to other books but is a response to them. These books, neither comps (nor craft books), point us to the story we want to tell as writers.

If I felt like I’d been writing my forthcoming novel, All This Can Be True, my entire life, well it’s because I was. I’d been writing it in response to two other novels that had burrowed so deeply within my psyche, my subconscious, that much of my own output over the years (several novels, numerous short stories) has responded continuously to their themes, their questions, until I was finally satisfied with my own response to them.

The two books that have made such an indelible mark on me? Ann Packer’s The Dive From Clausen’ s Pier and Kristin McCloy’s Some Girls. Not because of their prose, although they are certainly beautifully written, but because their plot and themes eerily mirror each other, and because they mirror what I’ve been exploring, consciously and subconsciously, in my own writing all of my life.

In Packer’s bestseller The Dive From Clausen’ s Pier, 20-something Carrie Bell is about to break up with her fiancé, Mike, when he is paralyzed from the neck down after jumping into shallow water off Clausen’s Pier. Carrie wrestles with staying with Mike before deciding to head, on a whim, to New York to pursue a career in fashion. But, like all well-plotted novels, the story doesn’t end there, and the reader is left to wrestle with what we owe to the people we love. Similarly, in McCloy’s second novel Some Girls, 20-something Claire moves to Manhattan in the 1980s, away from her boyfriend and her small hometown in New Mexico, in search of herself. Who she finds is her enigmatic, world-traveling next-door neighbor Jade, and in the end, the reader is left to wrestle with who and how we love the people we love.

Some Girls was published in 1994, a time when queerness was far from mainstream, so far that there’s no mention of it in the book’s synopsis. Therefore, I was shocked that Claire and Jade’s friendship was much more than that—in fact, intimate and erotic. I had begun to explore my own sexuality at the time in my writing—mostly in my high school and college notebooks, which were carefully tucked away in a box in the top shelf of my closet. In my stories, two friends, Claire and Amanda, consoled each other after breakups, hangovers, absent parents. At some point, however, Amanda fell in love with Claire⎯of course, Claire rejected her (I was not out yet myself), and then Amanda’s deeply internalized homophobia led her to act out in more self-destructive ways: promiscuity, more alcohol, drugs, a mirroring of my own identity at the time. In contrast, Claire and Jade’s coupling in Some Girls felt unburdened by this deep loathing, even if it lived in the floaty amorphousness of women who sleep with men but sometimes sleep with women. In fact, in 1994, before gay marriage, before the first lesbian kiss on television, even, their relationship felt quite revelatory.

And more than that, I wanted to be Claire. I had moved to the city after college (okay, Baltimore, not Manhattan, but way bigger than my high school town of 1,000), and I was ready to find my own Jade. Although I did not quite find her, I began my first long-term same-sex relationship, with a woman who was very smart but very emotionally unavailable. Who was also emotionally (and sometimes) physically abusive. A woman who I spent many years trying to leave. I wasn’t bound by tragedy to this woman, and it’s not as if there weren’t perfectly good reasons for me to leave, such as her affair with a coworker. However, I was bound by trauma. Like most victims, at the time, I had no idea what trauma bonding was. I only knew that I had lost my sense of self in this deeply dysfunctional relationship, to the point that I thought my job was to read my partner’s mind and keep her happy at all times. If I did, then my sense of self would be fulfilled in all the ways it hadn’t been growing up, when I’d tried (and repeatedly failed) to be the mediator of my own parents’ alcoholic, dysfunctional marriage.

While I was navigating this relationship with my now-ex, Ann Packer published her debut novel, The Dive From Clausen’ s Pier, in 2002. As I read, I marveled that Carrie could leave behind Mike, the now-quadriplegic fiancé she once loved, move a thousand miles away (before social media, even!), and try to find her own happiness, independent of a partner. As a reader, we are not spared the immediate enormity of Carrie’s situation. It’s right in the second paragraph: “Mike’s accident happened to Mike, not me, but for a long time afterward I felt some of that glow.” What does Carrie owe Mike? Although she hadn’t been strong enough to break up with him before a holiday weekend (before he took that fateful dive into shallow water), it’s not as if she pushed him off the pier in or suggested he do it. Her only crime was waiting too long to spring the news which, if anything, drives home the lesson of taking chances before it’s too late. Still, by the end of the novel, Carrie, after another difficult choice, finds an answer with which she’s able to live, one that gives her peace. One that’s right for her.

By my 30s, after 11 years together, I finally summoned the courage to leave my own partner. My writing at the time had begun to tackle similar themes: imprisonment—in one’s sexuality, in one’s relationships—and escape. Not just escape, but liberation. Escape has always felt to me more of an action, a reflex without reflection: to escape pain, we take our palm off the stove burner. Liberation is also an action, but also a conscious choice. I am not mindlessly avoiding pain; rather, I am gathering the courage to leave the pain of a codependent relationship so that I can heal, a paint that feels like conquering an addiction.

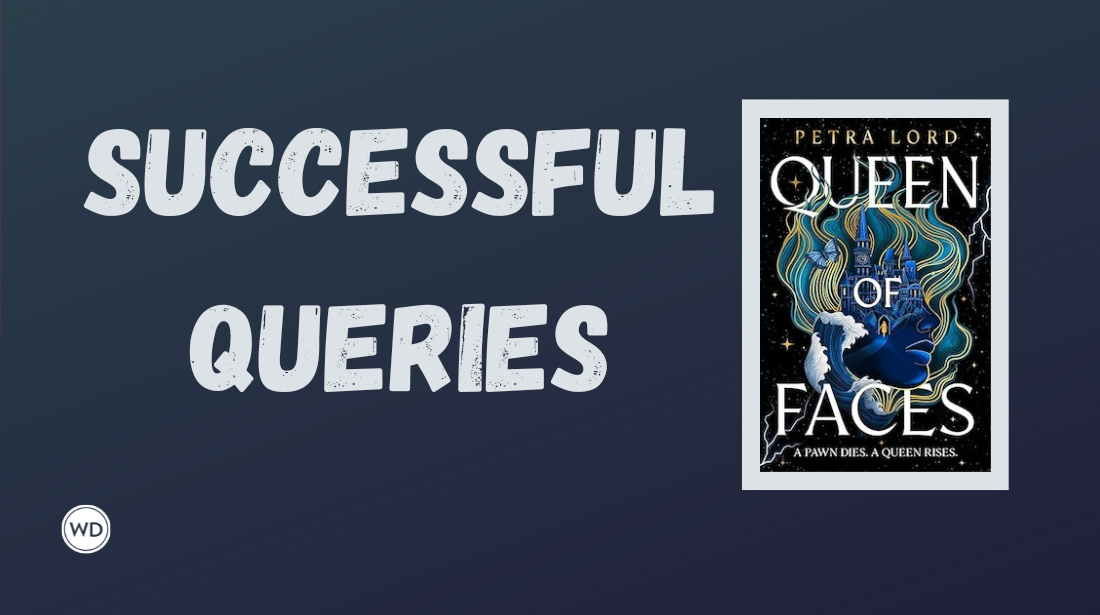

After two years of being single, I was able to enter another long-term (healthier) relationship, but I still wasn’t finished exploring the ties that bind in my own writing. In my forthcoming novel, All This Can Be True (Turner/Keylight), the novel opens with the protagonist, Lacie, on a plane with her husband, contemplating divorce, when he slumps over from a stroke. Unlike Dive’s Carrie, Lacie is a little older, 46, with two grown children—but she’s still caught wondering what she owes a loved one whose life has irrevocably changed. To complicate matters, Lacie becomes close to a woman, Quinn, she meets at the hospital, a woman who, unbeknownst to Lacie, harbors a secret that connects her to Derek.

I won’t tell you how it ends, but I hope the writing of this novel ends a chapter in my life that seems to have many sequels. Lacie, much like Claire in Some Girls and Carrie in The Dive From Clausen’ s Pier, is able to embrace her agency and create the terms of her own life. But what makes a relationship and what one owes that relationship are never easy questions. Perhaps we never solve them, or only solve them in novels, in real life merely finding temporary workarounds for whatever relationship we are in at the time. Characters experience seismic changes over the course of 85,000 or 90,000 words; it takes lifetimes, sometimes, for real people to experience change and, for generations, sometimes even longer.

Maybe these books are not just “personal comps” but seeds; their ideas helped forge a path in me that I was able to explore in my own writing and, as they say, visibility is everything. When I was growing up, the only reference to gay people was the one I found in the large health encyclopedia my mom kept under the coffee table when I was a kid. Although it didn’t outright demonize us, it wasn’t particularly encouraging of us, either. And even though there were a few pro-LGBTQ+ YA novels in the 1980s, like Nancy Garden’s Annie on My Mind, my childhood library did not carry it, and I didn’t learn of its existence until well into my 30s. Suffice to say, it blew my mind that not only Kristin McCloy was writing about queer girls in 1994, but that she was getting a starred review from Publishers Weekly.

Likewise, growing up, although there were a lot of books about women coming of age and finding true love, there weren’t a lot of books about the difficulties women faced in getting out of abusive relationships or even just relationships in which they weren’t particularly happy, even if they were home runs on paper. Ann Packer’s The Dive From Clausen’ s Pier was the first novel in which I felt the call of trusting one’ s gut. Even if it took me many years to trust my own, if I hadn’t seen these choices in the public sphere when I had, perhaps it would have taken me longer.

Still, I think this is the last novel I’ll write about these particular relationship dynamics. I still love Some Girls and The Dive From Clausen’ s Pier, and although writing has been a form of therapy, a way to see my own problems laid bare on the page to solve before the denouement, I find myself thinking about other people than myself, situations unlike my own. Maybe, like Claire, Carrie, Linney, and Lacie, I’ve finally turned the page.

Check out Jen Michalski's All This Can Be True here:

(WD uses affiliate links)

Jen Michalski is the author of three novels, most recently You'll Be Fine (2021), three story collections, and a couplet of novellas. Her work has appeared in more than 100 publications, including Poets & Writers, Writer's Digest, The Washington Post, The Literary Hub, Baltimore Magazine, McSweeney's Internet Tendency, The Cincinnati Review, and more, and her fiction has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize six times. She's the editor in chief of the literary weekly jmww and lives in Southern California.