The Reality of Self-Publishing: An Agent’s Perspective

Today, writers need to weigh their options carefully—and know what they’re up against. by Andrea Hurst

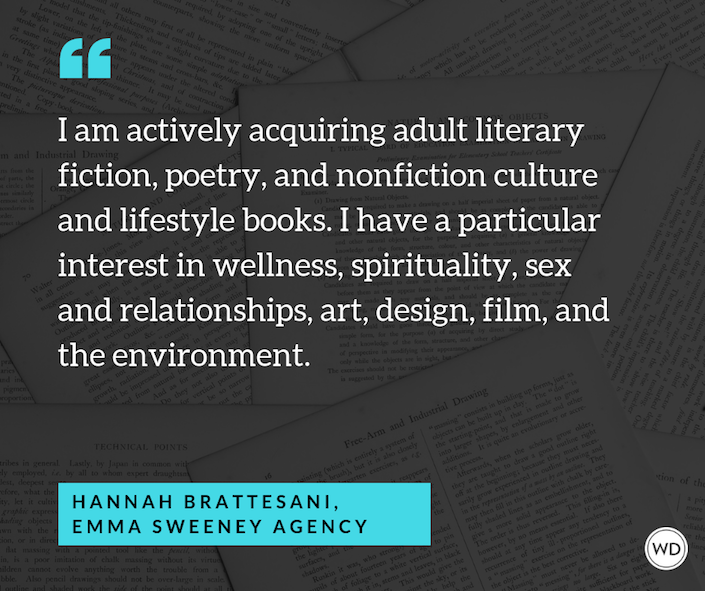

As a literary agent, I receive hundreds of query letters every month—and reject about 99 percent of them. Many aspiring writers dream of getting a book published, but for most it’s a tough road to navigate, and today’s economy is making it even harder to get a deal from a traditional publisher. These factors—coupled with the increasingly affordable and accessible choices for self-publishing—are prompting many authors to get their book out there on their own.

Indeed, self-publishing can be successful. Several recent bestsellers started out self-published before landing a mainstream deal and hitting it big: Rich Dad, Poor Dad,The Celestine Prophecy, Eragon and The Shack among them. But almost always, behind each break-out success you’ll find a dedicated, highly motivated author with an extensive marketing plan that’s being implemented on a full-time basis. What you hear about less often are the thousands of disappointed authors who have gone the self-publishing route only to end up with hundreds of unsold books in their garages.

When a submission to an agent states that the book was formerly self-published, that can be a red flag: If a book doesn’t sell well in its first printing, regardless of who or what house produced it, it’s very unlikely that another publisher will pick it up. When agents like me receive queries from a writer with a self-published book, we first ask how many copies it has sold and how long it’s been in print. We’re looking for one set of qualifications: a highly marketable hook and a product that has sold at least 5,000 books in (preferably) just a year or less on the market.

If you’ve self-published and generated good profits, consider all the pros and cons before making the decision to seek an agent to take it to a larger publisher. True, a large publisher can offer you much better distribution and higher visibility. However, you’ll face being put on a publisher’s timeline—and having to earn back your advance before you see additional income. This may be a welcome relief from the massive job of covering all aspects of the publishing yourself, but it’s also a big shift in strategy. And, of course, you’ll be asked to stop selling your current self-published edition at some point before the new one comes out.

Jennifer Basye Sander, author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Self-Publishing, self-published a small booklet called The Air Courier’s Handbook, which sold 5,000 copies, primarily through Internet and mail-order marketing efforts. Her total income was $40,000 with minimal expenses, so she made an excellent profit. She attributes this to finding and serving a clear niche market, planning a direct route to her audience and dedicating herself to marketing the product aggressively. Self-publishing can be the best option if you have a niche idea that’s directed toward a very targeted market and may not appeal to a large publisher. On the other hand, breakouts such as The Shack appealed to a broad range of readers, but reaching that audience would have taken much larger campaigns than most authors have the funding, time or expertise

to undertake.

If you’re up to the challenge (and equipped to meet it head on), self-publishing may be an excellent way for you to prove your book can sell and to begin building your career. But be sure to do lots of research in advance, avoiding publishers with hidden costs and shabby mediocre production quality. I can often spot a book that’s self-published at a glance, and not for any favorable reasons. I strongly suggest investing in a superior product that can compete in the professional publishing arena.

This article appeared in the March/April issue of Writer's Digest. Click here to order your copy in print. If you prefer a digital download of the issue, click here.