Fact Versus Truth in Writing Fiction

??Today’s post is from regular guest Susan Cushman. Visit her blog!— If you’ve been following the lawsuit filed by Ablene Cooper against Kathryn Stockett, author of The New York Times…

??Today's post is from regular guest Susan Cushman. Visit her blog!

--

If you’ve been following the lawsuit filed by Ablene Cooper against Kathryn Stockett, author of The New York Times bestseller The Help, I'm sure you saw this article in the February 17 issue of the Times: "A Maid Sees Herself in a Novel, and Objects."

?Ablene Cooper is

a 60-year-old black woman who works for Stockett's brother

and his wife, and the Times article says they encouraged her to sue

Stockett for "an unpermitted appropriation of her name and image, which

she finds emotionally distressing."

The name Stockett used for the

character in the book is "Aibileen." There are similarities in the lives

of the fictional character and the real person of Ablene Cooper. The

Times article also says, "The lawsuit, filed in Hinds County Circuit

Court, contends that Kathryn Stockett was ‘asked not to use the name and

likeness of Ablene’ before the book was published, though it does not

specify who asked."

Two years before this Times piece, I met Stockett at a reading/signing at Lemuria Books in Jackson (Miss.), where she read before her hometown crowd for the first time. Her work fascinated me; I came of age in Jackson, and grew up in the neighborhoods fictionalized in The Help. Stockett has received lots of criticism for the light in which she

portrayed blacks during this era, even for her use of dialect, which I thought was point on.

I read the New York Times article with interest and wanted to write a post about it, but I felt inadequate to address the legal issues. So, I asked John D. Mason, who is a literary agent and a literary/art and entertainment attorney with The Intellectual Property Group, PLLC, in Washington, D.C. to answer a few questions about the situation.

Was this a dangerous move on Stockett's part to

use such a similar name and assimilations of image? ??

Generally, it was not wise for an author to have a character name so similar to that of a living person and to also have facts so closely match real life in fiction (I am using public reports on the lawsuit for my facts).

These types of cases are expensive and fact intensive, and frequently it is difficult to establish damages. I would be surprised if this went to trial and Ms. Cooper was ultimately successful in achieving a significant recovery, although I have been surprised many times before.

As a general rule, fiction authors control their work and so doing something so close to reality just does not make sense. If Ms. Stockett had thought about it and changed the name and facts only a little bit, this wouldn't be an issue at all. Better safe than sorry.

The Times article says, "Though the character of Aibileen is portrayed in a sympathetic, even saintly light, she endures the racial insults of the time, something that Ms. Cooper said she found ‘embarrassing.’” I read the book, and having grown up in "North" Jackson, Mississippi, during the 50s and 60s, I found the descriptions of the times to be very accurate, and Stockett's voice to be non-judgmental. How legitimate are Ms. Cooper's claims that the book harmed her? What do you think the chances of the plaintiff winning this suit are? And, should Ms. Stockett have done more to protect herself? ?

I don’t think it is likely that this case will go to trial or that Ms. Cooper will receive a significant award of damages if it does and she is successful.

This is a name and likeness/right of publicity case and those tort claims arise generally from an individual's right of privacy. This lawsuit is most likely what is known as an action for appropriation of Ms. Cooper's name and likeness, which is an action a non-celebrity brings for unauthorized use of their name and likeness, generally where there is no commercial use involved.

A right of publicity case generally is one where a person is a celebrity or uses their persona in a commercial sense and thus they have a property interest in controlling exploitation of their persona or name and likeness. The goal of the state laws which create the action for appropriation of name and likeness cause of action are to prevent emotional/reputational injury and protect people from invasions of their privacy (it does not appear that this is a false light case).

I believe that Ms. Stockett's attorneys will argue that she has first amendment defenses, that any similarities are incidental and de minimis in their impact, if any, on Ms. Cooper, and that her artistic expression is only coincidentally and not intentionally similar to Ms. Cooper's name and/or likeness. (It should be noted that a likeness is generally understood to literally be the face of an individual, which does not appear to be an issue here).

If Ms. Cooper is successful in convincing a jury or judge that the use made by Ms. Stockett is a misappropriation of her name and likeness and violation of her right of publicity, she would be entitled to her actual damages, which may be difficult to quantify and prove by evidence but could arguably be an apportioned amount of profits attributable to the commercial exploitation of her name and likeness or right of publicity.

If there is a showing of bad faith on the part of Ms. Stockett—the reason the complaint notes that Ms. Stockett was asked not to use or appropriate Ms. Cooper's persona—then Ms. Cooper may be entitled to a trebling or other enhancement of her actual damages.

Similarly, in the event of such a bad faith finding, Ms. Cooper may also be entitled to attorney's fees and costs under the Mississippi statute. ??

All of the foregoing gets very complicated and the bottom line is that it will be an expensive effort and trial with, in my opinion, a potentially small likelihood of success and little likelihood of recoverable damages. I think it is most likely that there will be a settlement based on the cost of defense. Essentially, I think it is likely that Ms. Stockett will buy peace based on how much it will cost to defend the entire case through trial.

We've been discussing the risks involved in portraying real people in a negative light in fiction-writing. Are authors "safe" from lawsuits if they change the names of the real-life people they portray in nonfiction books, like memoirs?

Not necessarily. If the people they are writing about are sufficiently identifiable, even after changing the name the author may be exposing his or herself to claims for libel, false light, public disclosure of private facts and related cases. Obviously, the truth is usually a good defense to some of these types of claims, but there can even be situations where disclosing true facts can be actionable in certain jurisdictions. If you are unsure, best to consult a literary attorney to conduct due diligence on the manuscript. This is a great discussion of the issue.

?--

John D. Mason lectures 10–20 times a year on legal issues for artists and writers, and will be among the faculty at the 2011 Memphis Creative Nonfiction Workshop in September, along with his client, Bob Cowser, Jr. They’ll be doing a presentation on author-agent relations and other legal issues that writers need to know about. (Registration is open!)

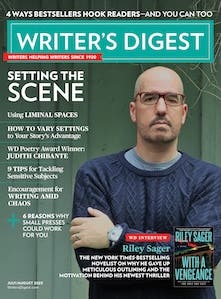

Jane Friedman is a full-time entrepreneur (since 2014) and has 20 years of experience in the publishing industry. She is the co-founder of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and is the former publisher of Writer’s Digest. In addition to being a columnist with Publishers Weekly and a professor with The Great Courses, Jane maintains an award-winning blog for writers at JaneFriedman.com. Jane’s newest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press, 2018).