READER QUESTION: Why shouldn’t I write an “origin pilot?”

Hey, guys— First off, I want to give a HUGE THANK YOU to E. Daniels and everyone else who submitted questions to Eric, our host at Reality Binge, for him…

Hey, guys—

First off, I want to give a HUGE THANK YOU to E. Daniels and everyone else who submitted questions to Eric, our host at Reality Binge, for him to answer on his funny blog. You can submit whenever you want, so please… keep ‘em coming!

Secondly, wanted to take a few moments to answer a great question I received the other day.

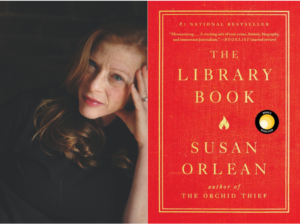

This question comes from Susan, who took my pilot writing class last week. Susan writes...

“You recommend not writing an ‘origin pilot’ (a la Lost), but writing a pilot that could be episode 100 or episode 1. But aren't pilots where the main character moves to Alaska (Northern Exposure) or gets hit on the head (Samantha Who?) origin pilots? Or do you mean a literal creation of a whole new world type of thing?”

Great question, Susan! To get to that answer, let’s take a quick step back to catch people up…

As I said last week last week, many writers often make the mistake of thinking that a pilot is simply the first episode of a TV series, and your job in writing a pilot is to write the beginnings of a story and characters that make people want to keep watching.

While this is PART of what a pilot is, it’s only partially/somewhat/occasionally accurate.

In truth, a pilot is designed to be a prototype of a typical episode or your series. Yes, it’s introducing your audience to the world of your story (and before your show is on the air, your pilot’s “audience” consists mainly of network execs who decide whether to air your project at all), but it’s also meant to show networks how the show will work in series. Which means your job is not only to launch a story that can sustain itself for years to come, but to illustrate how that series will generate and tell stories whether it’s at episode 10 or episode 500.

Thus, if every episode of your show is a close-ended story in which your main character, a detective, solves an art heist, your pilot needs to show that detective solving an art heist. If every episode of your series shows a group of friends helping each other through wacky dating situations, your pilot needs to show that same group of friends helping each other through funny dating situations.

In other words, while your pilot is—in some way—unlike any other episode of your series (because it’s the beginning of your story), it must also work just like every other episode of your series.

So, now that we understand this, there tend to be two types of TV pilots: origin pilots and "traditional pilots" (to be honest, I’m not sure if non-origin pilots have a special name, so I just call them “traditional” pilots).

Traditional pilots work just like a regular episode of the series. In fact, some—like the Everybody Loves Raymond pilot—are nearly indistinguishable from regular episodes. They spend very little time introducing characters, setting up stories, etc. They just throw readers/audiences right into the world and start the show.

Origin pilots begin at the VERY BEGINNING of the story. Jericho kicked off with a nuclear attack. Grey's Antaomy begins on the day Meredith meets the other interns and McDreamy.

Different pilots work differently. The question is: WHICH IS MORE SELLABLE OR MORE ATTRACTIVE TO NETWORKS AND STUDIOS?

The answer, almost unequivocally, is: “traditional” pilots. Remember, the true job of a pilot is to show audiences—including network buyers—how the episodes works on a regular basis, and traditional pilots do this MUCH BETTER than origin pilots, which have so much “pipe to lay,” or story to set up—that they frequently don’t work like subsequent episodes.

(In fact, sometimes the series’ original pilot never airs… or airs out of order… because the network simply wants to jump right into the meat of the story. Firefly and Cavemen both aired their pilots later in the series. Ed shot a pilot, decided not to use it, then cut it into an quick montage that opened the first episode to set up the story.)

Now, Susan, you ask about pilots like Northern Exposure and Samantha Who?, where Joel moves to Alaska or Sam gets hit on the head and goes into/awakes from her coma.

Many pilots, obviously, are indeed telling the beginning of a story, so they can’t scrap ALL the elements of an origin pilot. After all, they still need to START THEIR STORY (by moving Joel to Alaska or putting Sam in the coma). But they also need to show how the episodes work. Thus, they usually set up their story as quickly as possible, but they also work hard at illustrating how future episodes will play out.

The CSI pilot, for instance, began with a new detective (Holly) joining the CSI team. It was a new day for the CSI gang… they had a new member. (This also allowed the storytellers to introduce the other people, places, and situations organically, since Holly was just meeting them for the first time.) But the rest of the episode then followed the crew as they solved what would become a fairly typical CSI mystery. (And they even killed off Holly, our entrée to the world!)

Similarly, the Grey's Anatomy pilot begins with the interns meeting each other for the first time… but it also has typical close-ended patient stories (Meredith and the girl with seizures, George and the open-heart patient, etc.).

Other pilots don’t bother setting up story at all. The Cosby Show, like Everybody Loves Raymond, just plunged right into its basic family-life storylines.

Your job, Susan, is to decide which type of pilot works best for the story you’re telling. I would never say: "NEVER write an origin pilot." Some shows, like Lost, require more origin set-up than others. Others, like The Cosby Show, can get away with diving right in. You need to write whatever story launches your story the best. HOWEVER...

The most important thing to keep in mind is this: a pilot isn’t designed simply to be the first step in a longer story, it’s designed to be a selling tool that shows network buyers how that series will work on a regular basis.

(Think of yourself as a door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesman. You want to wow your potential buyers with something flashy, cool, and sexy... but you also need to show them how the vacuum works. If they don't see how the machine will work on a regular basis, it doesn't matter how cool and attractive it is... they won't buy it.)

If you can remember that—even if you’re telling an origin story—you’re well on your way to writing (and selling!) a successful pilot.

I hope that answers your question. And please, everyone, if you have others, don’t hesitate to shoot me an email: WDScriptNotes@FWPubs.com!

Talk to you soon…

Chad

Jane Friedman is a full-time entrepreneur (since 2014) and has 20 years of experience in the publishing industry. She is the co-founder of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and is the former publisher of Writer’s Digest. In addition to being a columnist with Publishers Weekly and a professor with The Great Courses, Jane maintains an award-winning blog for writers at JaneFriedman.com. Jane’s newest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press, 2018).